From the towering skyscrapers that define our skylines to the intricate chassis of a race car, welding is the invisible backbone of our modern world. It is the fundamental fabrication process of joining materials, typically metals or thermoplastics, by using high heat to melt the parts together, allowing them to cool and fuse into a single, robust piece. While Sir Humphry Davy’s discovery of the electric arc in 1800 laid the groundwork for modern techniques, the concept of joining metal is ancient. Today, welding has evolved into a diverse field of highly specialized methods, essential for everything from home repairs to advanced aerospace manufacturing.

But how does this process of permanently bonding materials actually work, and what are the different methods welders use to achieve it?

The Core Principle: Controlled Melting

At its heart, welding is a game of controlled melting. The primary goal is to heat the edges of two or more workpieces until they liquefy, forming a shared pool of molten material called a weld pool. This is the key difference between welding and other joining methods like soldering or brazing, which use a lower-temperature filler metal to act as a glue without melting the base materials.

Once the weld pool is formed, it is allowed to cool and solidify, creating a metallurgical bond that can be as strong, or even stronger, than the original materials. While the concept is straightforward, the execution varies greatly depending on the source of energy—be it an electric arc, a combustible gas, a laser, or even friction—and the materials being joined.

The process often involves other key elements:

- Filler Material: In many cases, a filler metal is added to the weld pool to add strength and volume to the joint. This can come in the form of a wire, rod, or granular powder.

- Shielding: The molten weld pool is highly reactive to elements in the atmosphere, like oxygen and nitrogen, which can cause defects and weaken the joint. To prevent this contamination, a shielding gas or a protective slag from a flux is used to isolate the weld area.

With these fundamentals in mind, let’s explore the most common families of welding processes used today.

Major Types of Welding

Welding techniques are typically categorized by their energy source. Understanding these categories reveals the unique principles and applications of each method.

I. Arc Welding

Arc welding processes are the most common and are likely what most people picture when they think of welding. These methods use an electrical power supply to create an arc between an electrode and the base material, generating intense heat to melt the metals.

A. Stick Welding (SMAW) Shielded Metal Arc Welding (SMAW), commonly known as stick welding, is one of the oldest and most versatile methods. It uses a consumable electrode “stick” coated in a material called flux. When the arc is struck, the electrode melts to become the filler metal, while the flux coating vaporizes to create a shielding gas and forms a protective layer of slag over the weld. With no need for an external gas tank, stick welding is highly portable, making it ideal for outdoor repairs, construction, and working in tight or awkward positions.

B. MIG/MAG Welding (GMAW) Gas Metal Arc Welding (GMAW), widely known as MIG (Metal Inert Gas) or MAG (Metal Active Gas) welding, is the workhorse of the industrial world. Often called the “point-and-shoot” of welding, it uses a continuously fed wire that acts as both the electrode and the filler material. As this wire is fed through a welding gun, a shielding gas is simultaneously released to protect the weld pool. Its relative simplicity, speed, and adaptability make it a top choice in manufacturing, automotive repair, and construction.

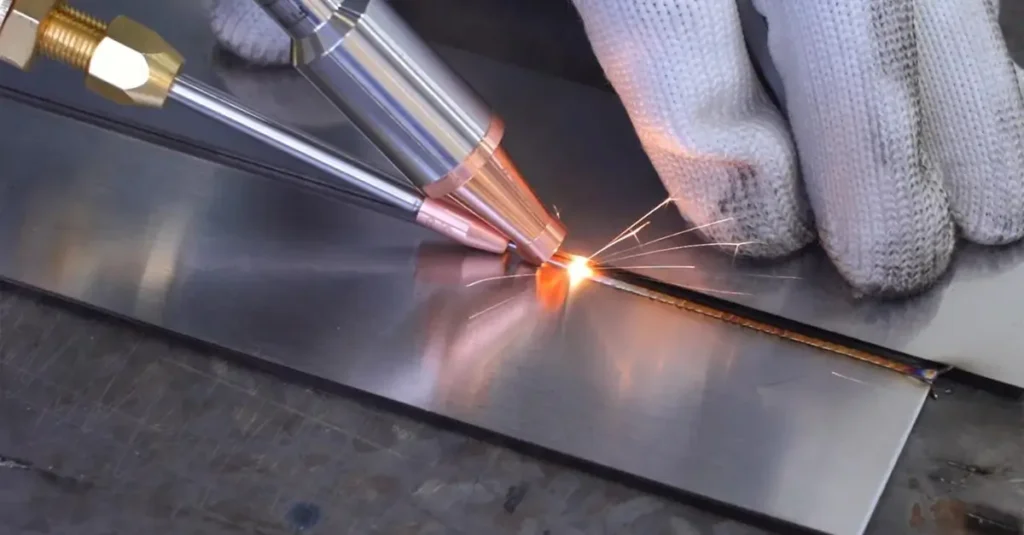

C. TIG Welding (GTAW) If MIG is the workhorse, Gas Tungsten Arc Welding (GTAW), or TIG, is the artist’s brush. This process is renowned for creating clean, precise, and high-quality welds. It utilizes a durable, non-consumable tungsten electrode to generate the arc, and the filler metal is added separately by hand. This separation of heat source and filler material gives the welder ultimate control, making TIG essential for applications where precision is paramount, such as in the aerospace, nuclear, and automotive industries.

D. Flux-Cored Arc Welding (FCAW) Flux-Cored Arc Welding (FCAW) blends the efficiency of MIG with the outdoor versatility of stick welding. It uses a tubular wire electrode filled with a flux agent. As the wire melts, the flux provides shielding from the atmosphere. Some variations, known as dual-shielded FCAW, also use an external shielding gas for extra protection. This robust process is excellent for heavy-duty applications like shipbuilding, structural steel, and underwater repairs, as it performs well on thicker, less-than-perfectly-clean materials.

II. Gas and High-Energy Welding

A. Oxy-Fuel Welding One of the earliest industrial welding methods, oxy-fuel welding, uses the combustion of a fuel gas (commonly acetylene) with pure oxygen to produce a high-temperature flame. It doesn’t require electricity, making it useful in locations without a power source. While largely superseded by arc welding for many applications, it remains valuable for brazing, soldering, and cutting, as the same equipment can be adjusted to slice through steel with ease.

B. Plasma Arc Welding (PAW) Think of Plasma Arc Welding as TIG’s supercharged cousin. It also uses a non-consumable tungsten electrode, but it forces the shielding gas through a much tighter nozzle, constricting the arc and creating a highly focused, superheated jet of plasma. This process can reach astonishing temperatures, around 28,000∘C, hot enough to melt any known metal with surgical precision. The concentrated heat results in a narrow weld bead and minimal distortion, making it perfect for automated, high-precision tasks.

III. Resistance Welding

Resistance welding techniques generate heat through the electrical resistance of the materials being joined. They use a combination of high pressure and a strong electrical current to fuse workpieces together.

A. Spot Welding (RSW) Resistance Spot Welding is the dominant process in high-volume manufacturing, especially in the automotive industry for assembling car bodies. Two copper electrodes clamp overlapping metal sheets together while a powerful current is passed through them. The metal’s resistance to the current flow generates intense heat at the point of contact, creating an instantaneous fusion nugget. The process is incredibly fast, clean, and easily automated with robotics.

B. Seam Welding Seam welding is a variation of spot welding that creates a continuous, leak-proof weld. Instead of pointed electrodes, it uses two rotating wheels that roll along the workpiece, applying pressure and current to create a series of overlapping spot welds or a continuous seam. This method is ideal for manufacturing products like fuel tanks, radiators, and steel drums.

IV. High-Energy Beam Welding

A. Laser Beam Welding (LBW) Laser Beam Welding utilizes a highly concentrated beam of light as its heat source. The laser’s immense power density allows for deep, narrow welds with a very small heat-affected zone, minimizing material distortion. This precision and speed make LBW a go-to process for automated applications in the medical device, electronics, and automotive industries where fine tolerances are critical.

B. Electron Beam Welding (EBW) In this highly advanced process, a beam of high-velocity electrons is fired at the workpieces in a vacuum chamber. When the electrons strike the material, their kinetic energy instantly converts to thermal energy, causing the metals to melt and fuse. The vacuum prevents any atmospheric contamination, resulting in exceptionally pure and strong welds. EBW is used for critical, high-performance applications in aerospace, nuclear power, and advanced automotive components.

V. Solid-State Welding

Friction Welding Stepping away from arcs and flames, friction welding is a solid-state process that generates heat through pure mechanical force. It doesn’t melt the material in the traditional sense. Instead, by rapidly rubbing, rotating, or vibrating two workpieces against each other under immense pressure, the friction creates enough heat to plasticize the metal at the interface. This allows the materials to forge a powerful bond without ever reaching a fully molten state. This clean, efficient method produces no fumes and is used to join diverse materials for components like axle tubes, drill bits, and hydraulic piston rods.

A Commitment to Safety

The power to melt metal comes with inherent risks. Welding produces intense ultraviolet light, high heat, and potentially harmful fumes. Therefore, safety is non-negotiable. Proper Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)—including an auto-darkening welding helmet, flame-resistant clothing, and gloves—is absolutely essential.

Modern technology is continually advancing welding safety. Automated systems and robotic arms can now perform complex welds in hazardous environments, removing the human operator from immediate danger. While skilled specialists are still vital for programming, oversight, and quality control, automation ensures that the most dangerous tasks can be completed with greater consistency and safety.

The Ever-Evolving Future of Fabrication

From the simple forge welds of the Bronze Age to the computer-controlled laser systems of today, welding has been a constant engine of innovation. It remains an irreplaceable tool for both hobbyists and global industries. As technology progresses, with developments in hybrid welding processes and the ability to join new and exotic materials, welding will continue to shape the future of engineering and manufacturing, building our world one strong, permanent bond at a time. At KKraft RADIX, we are here to help you join your metal and engineering projects. Reach out to us on steel@kkraftradix.com for details.